“He really had been through death, but he had returned because he could not bear the solitude.” ― Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude.

In April of 2014, I was crying in my dark apartment in Midtown Sacramento. I had walked home from my internship at an art gallery. I had closed down the place in a stupor. I walked home feeling numb and didn’t feel tears running down my cheek until I turned on G street.

G — for Gabriel.

One of my childhood heroes had died.

When I arrived to the United States at the age of 15, I was bored out of my mind. I moved with my immediate family from the city of Aguascalientes, Mex., to southside Stockton, Calif., by Main Street, just a few blocks away from the Fair Oaks Library. That library was my only consolation to feeling completely misplaced, intimidated, and trapped in this country, which was new to me at the time. I had read Gabriel García Márquez’ “One Hundred Years of Solitude” already, but that year, away from my home, I devoured all his other available novels at Fair Oaks. Mexico had been the author’s refuge in the 1960s, and the country inspired him to start writing his most acclaimed novel. And in 2005, he was my refuge.

I am sure I am not the only one person who felt this way, but magical realism shaped the way I saw the world as a young teenager, and subconsciously I was also very influenced by García Márquez’ criticism on imperialism.

Although I was surprised that his collection ended up in an American institution, I was glad to hear that it was at the University of Texas, which is making the collection available to the public online. The collection includes ten manuscripts, fourty photo albums, twenty scrapbooks, five computers, and several boxes of correspondence.

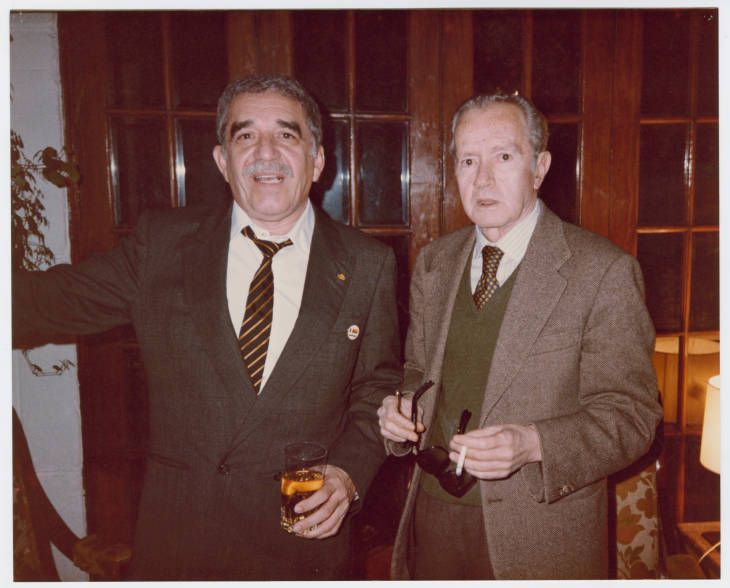

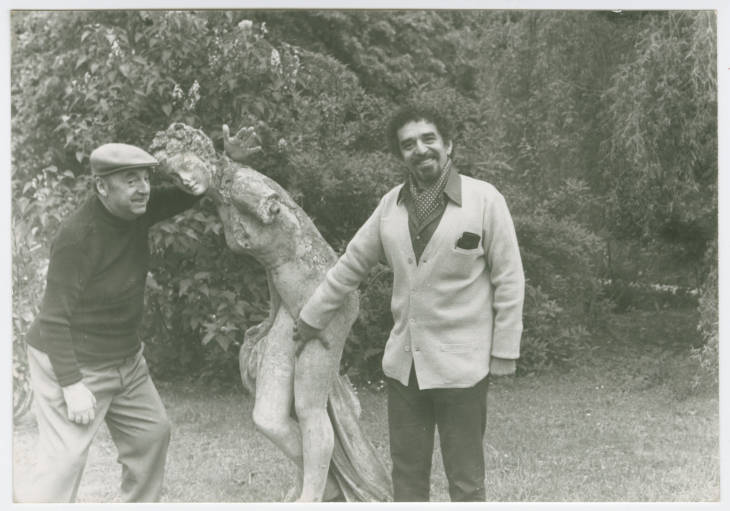

Gabriel García Márquez and Juan Rulfo, 1983

Gabriel García Márquez and Juan Rulfo, 1983

After digging around the online archive I picked a few of my favorite archived items, including this photograph of García Márquez and Juan Rulfo, who wrote “Pedro Paramo,” another classic I fell in love with in my early teenage years.

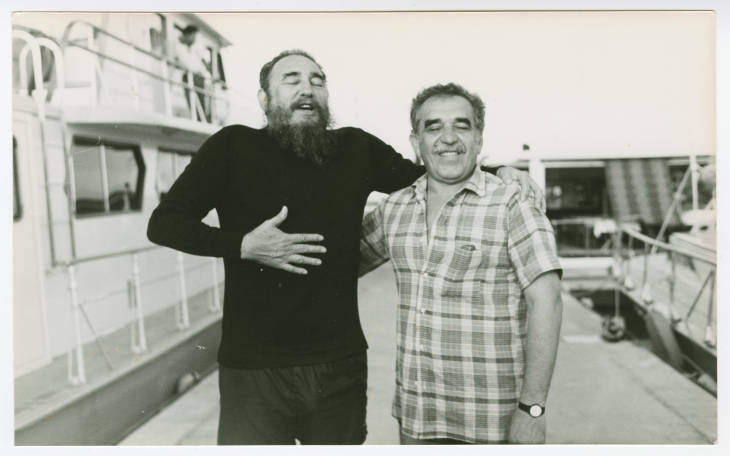

Below is one of many pictures of García Márquez with the revolutionary leader Fidel Castro. They met in 1959 and developed a friendship when Castro mentioned a correction on a speed boat calculation in one of García Márquez’s books, which propelled the author to send his manuscripts to be copy edited by Castro.

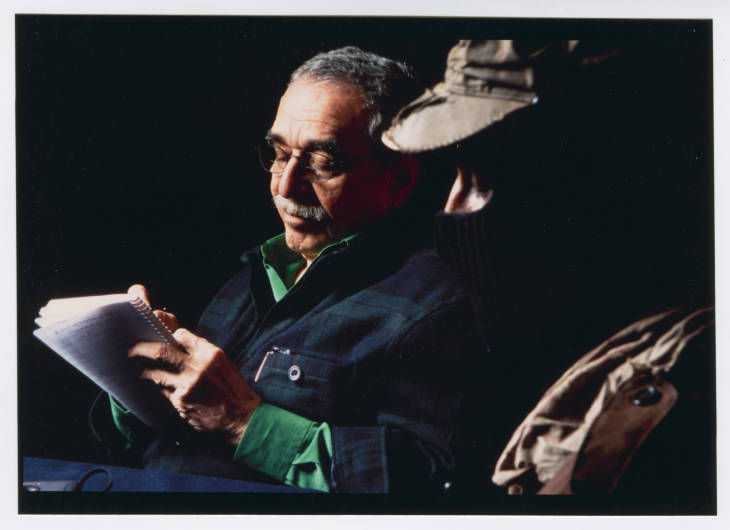

García Márquez and Fidel Castro, Not Dated

García Márquez and Fidel Castro, Not Dated

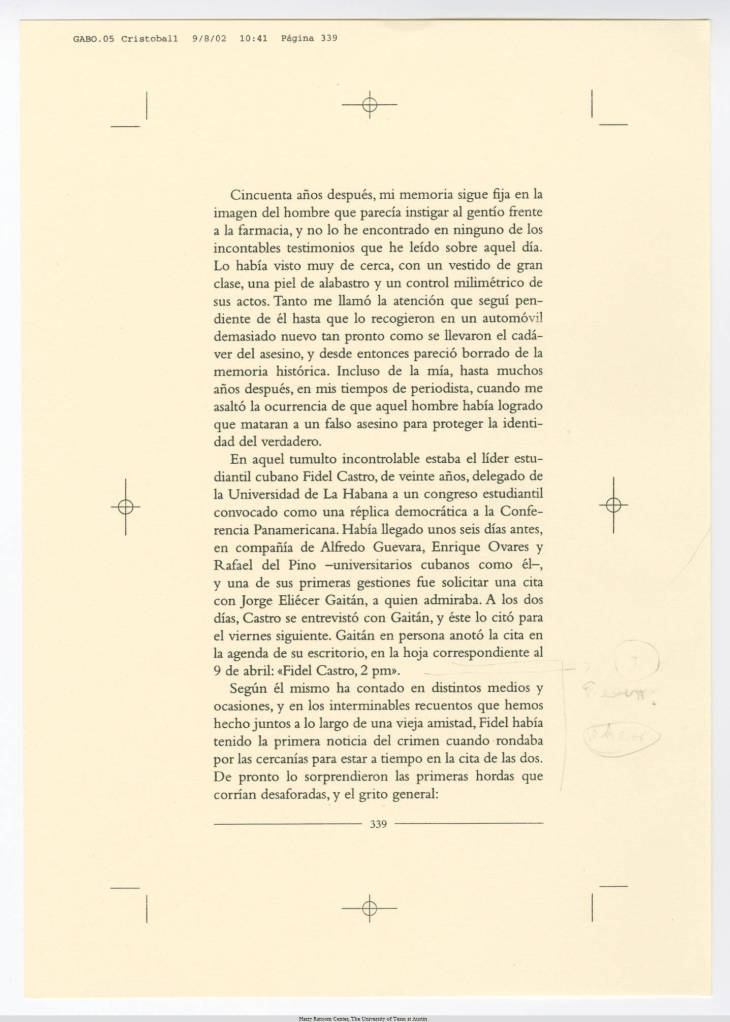

Following is a section of “Vivir Para Contarla,” in which Fidel Castro is mentioned. García Márquez describes him as a thin, 20 year old leader of the Cuban student congress of the University of Havana. Both Garcia Marquez and Castro were in Colombia during the assassination of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán Ayala, a populist candidate for presidency in 1948. Through the narrative of that day, the start of a tumultuous and violent political period in Bogota, García Márquez refers to Castro as an old friend who he shares interminable memories with.

“Vivir Para Contarla,” Image 193, 2001

“Vivir Para Contarla,” Image 193, 2001

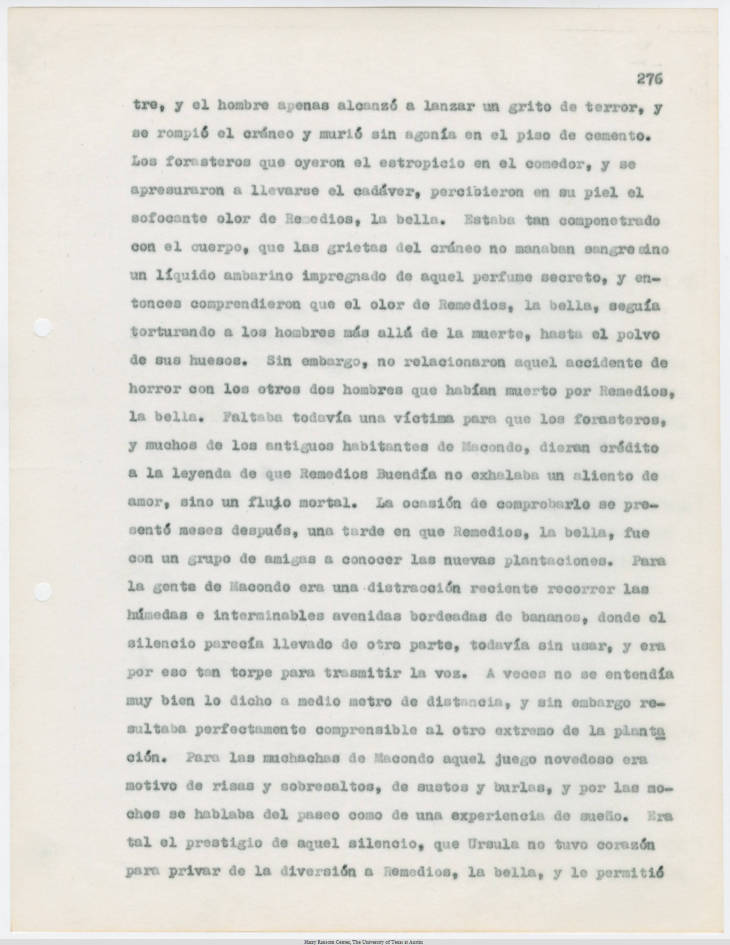

Below are a few printing proofs of “Cien años de Soledad,” where Remedios la bella, my favorite character, is talked about. Remedios is one of the most interesting characters made up by García Márquez, she is a beautiful and pure woman whose beauty charms men, but all those who procure her end up tragically dying. The case and personality of Remedios was always seen from another character’s perspective, she was deemed an imbecile, a saint, and a unintentional femme fatale, all because her character set her unfit for domestic life, a man’s love, and even traditional feminine clothing. In the passage below Remedios ascends to heaven without dying while hanging bed sheets out to dry.

“Cien Años de Soledad,” Image 277, 1966

“Cien Años de Soledad,” Image 277, 1966

García Márquez & Subcomandante Marcos, 2001

García Márquez & Subcomandante Marcos, 2001

García Márquez and Pablo Neruda, 1973

García Márquez and Pablo Neruda, 1973

While searching the collection I was struck with the hope that Gabriel García Márquez continues influencing Latin American readers of all ages to experience surrealism and realism, and to create artistic identities to share with one another. This inspiration is especially necessary while living in the politically tumultuous times of today, which is comparable to the instability of many Central and South American countries during the 60s, causing authors like García Márquez to leave their homelands.

García Márquez’ collection found a new home in the United States, where it is definitely needed, to be available to us, the millenial youth trying to have influence and visibility in the contemporary arts, literature, and politics of our time. Gabriel García Márquez is our lineage, a window into our culture, and an inspiration to explore the possibilities of a world where struggle, passion, and beauty, align and belong to one another.