*This post originally appeared on Restore the Delta’s blog, and is the first installment of an on-going, inter-organizational series of reflections from COP21 by activist Ryan Camero. Parts 2, 3, and 4

PARIS – Today marks the ending of the first week of the Conference of Parties (COP21) and the beginning of its second week. More than 200 nations of the world have come together to unify and to take action against global climate disaster.

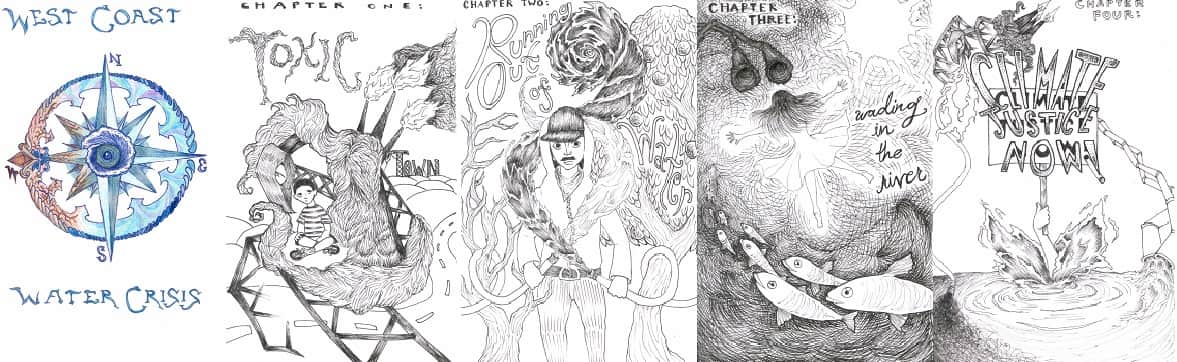

So here in Paris, at COP21, the international negotiations seeking a universal agreement on climate, my hope is to spark positive, life-saving ideas through art and storytelling. I am here to tell the story of my hometown’s river.

I live alongside the San Joaquin River, one the major rivers of the San Francisco Bay-Delta.

For decades, the San Joaquin has supported a massive industrial agriculture industry. Parts of the river go dry partly by drought and by over-extraction. Five times more water is promised to users than actually exists, and it hardly looks the same from one side to the other in its 417-mile lifeline. It’s no mystery why it is referred to by CNN as the most endangered river in America.

The last few days have been a multi-layered whirlwind, meeting some of the most inspiring and diverse youth activists gathered together from across our entire planet. We all have our hearts wrapped up in this work for our own local and personal interests with a determined spirit and a moral compass locked in stone; alas, despite our resilience, we all see our economic and social systems failing, and the ecological one in which we depend on will shatter irreversibly if we do not make this period of time worthwhile.

Through this experience, I have many stories to tell about how the global ecological crisis is impacting my home waterway. It is affirming and heartbreaking to know we all hold stake in this heavy, historic time. I hope that art can help tell my story.

I think the plight of the artist is nurturing an idea that wants to exist, and going through the process of communicating that idea from mind to reality. Without creativity, these ideas would be trapped in oblivion without any way to express themselves.

That oblivion, full of neglect and erasure, is a terrifying space. If an idea is never known, it will never hope to be created, let alone understood.

Photo by Matt Maiorana.

Photo by Matt Maiorana.

A recurring theme I’ve grown to understand in different parts of my life centers on this oblivion—the idea of conceptual and cultural erasure, and all the reverberating effects that come with that.

I’ve started to see the concepts of forgetting and losing in terrifying ways: growing up a Filipino-American in the United States, I struggled early on with assimilating into American culture. I was bullied for the color and culture of my skin in a predominantly white-centered world. Consequently, I grew up hating myself and my own ways of being. Looking back, the internalized racism I had in myself is appalling, especially as a child, and now I yearn to remember the erased history of my ancestors. Even here, at the COP, where the island nation of the Philippines is named is the third most vulnerable nation to climate change, I feel disconnected from my roots as a Filipino. Still, I continue to support the battle against coal-fired plants I’ve never seen and typhoons I’ve never known.

In that same sense, California’s forgotten and mistreated waterways have felt this oblivion. Take, for example, the San Francisco Bay-Delta, the largest estuary on the West Coast of the Americas: These rivers channel a crucial portion of the state’s water supply, yet their value in an ecosystem is reduced as a disposable backwater by Governor Jerry Brown’s proposed twin tunnels. These thirty-five foot tunnels stretch forty miles from Sacramento to Tracy, would extract about 60,000 gallons of freshwater per second from the waterways in order to send it to corporate desert agribusinesses and oil companies (such as the largest fruit and nut tree grower Paramount Farms, Wonderful Orchards, and California’s largest oil producer Aera Energy, both Bakersfield-based) to control even more water in the middle of this crippling drought.

So here we are, wrestling with our hopes, in this disorienting space of briefings, meetings, acronyms and policy text. We carry our voices like pens drawing ideas to protect our beautiful world from the throes of exploitation and corrupt, corporate deceit. We offer our personal fragments of climate justice stories and piece together a mosaic of movements, and I can’t think of a better way to start drawing power.

Cover photo courtesy of SustainUS