We must’ve moved about five times in five years. Every Christmas we lived in a different house. Since we moved to Stockton, California, my parents were able to upgrade our family into bigger homes. First we stayed with my grandparents, then a two bedroom, then three, until we each had our own rooms. Once we left Mexico, it seemed as if we just kept migrating farther North.

I hated moving, but I did enjoy having more space—as a teenager, that was very important.

My parents bought their first home on Eight Mile Rd. A single story, cookie-cutter, 20-year-old home. A cherry tree and lawn in the front, enough space to fit three cars in the garage, and there was even a jacuzzi in the back.

The location wasn’t great. We weren’t in the middle of nowhere. We were at the city limits of nowhere, where new hastily-built homes were sewn into the soil to meet market demand, where your neighbor was whatever crop was in season. I played in the surrounding fields where the rows of crops seemed endless, until I learned about the harmful effects of pesticides.

It was a developed desert, nothing but endless rows of homes, giant parking lots, and every big box store that you find in suburbia. Welcome to Any Suburb, USA. Growing up with nothing to do but leave. And you couldn’t even do that unless you had a car. We drove at least 10-15 minutes for groceries. But it didn’t matter; my family finally settled down in the nice part of town. I wouldn’t have to move again. Finally, I had my own room.

Three years later, we moved into a smaller house. My parents lost their dream house during the 2008 housing market crash. They payed $450,000, and when we left in 2009, it wasn’t even worth half of that.

From Downtown to Uptown and Suburbia

Nearly five months ago, I wrote about the racist practice of redlining in America’s neighborhoods, including Central Valley cities, such as Sacramento, Stockton, and Fresno. Following World War II, FDR’s New Deal America invested heavily on infrastructure and providing homes to soldiers. These policies encouraged racism in real estate by denying loans and investments to areas which experienced “infiltration of ‘Mexicans, negroes, and orientals.” This practice of redlining mixed areas steadily decreased property values of the urban core, where most people of color resided, while suburbs and businesses expanded to the outer rings.

Shortly after, the construction of the Interstate Highway System became the scalpels that dissected what was left of these diverse neighborhoods. Those who could afford it—mostly whites—migrated to suburban communities (this came to be known as “white flight”), with convenient newly constructed highways connecting them. Those who stayed were left even more disenfranchised than before and vulnerable to environmental hazards, property degradation, and lack of access to economic growth for decades.

This historically rich and diverse community was destroyed for the sake of convenience.

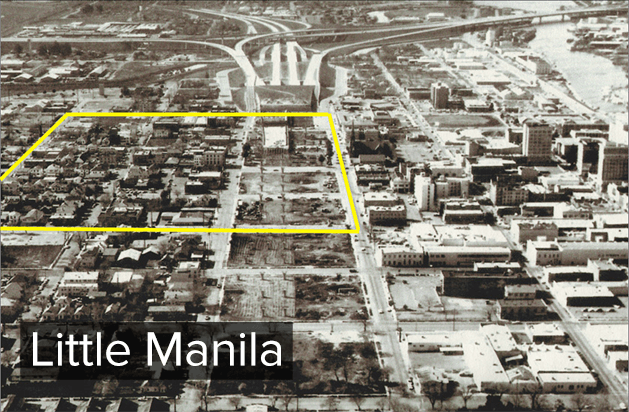

Lange Luntao wrote a powerful article of the destruction of Little Manila in Stockton, once home to the largest population of Filipinos outside of the Philippines. All that is left of the neighborhood and its memories is a stretch of concrete that connects I-5 with 99 called the Crosstown Freeway. This historically rich and diverse community was destroyed for the sake of convenience. The story is nearly identical in most cities with concentrated communities of color including Sacramento’s West End, West Fresno and its Chinatown, San Francisco’s Fillmore, and many others.

In this image from the 70s, you can see the construction of the Crosstown Freeway cutting through what was left of Little Manila (in yellow), Chinatown, and other historically diverse areas of Stockton.

In this image from the 70s, you can see the construction of the Crosstown Freeway cutting through what was left of Little Manila (in yellow), Chinatown, and other historically diverse areas of Stockton.

Eventually, the passing of the Fair Housing Act of 1968 at the height of the Civil Rights movement put an end to the policies and institutions that were explicitly discriminating against people of color in housing.

It’s been nearly 50 years since redlining became illegal; what has changed?

Short answer: not much.

Still Ill: A Legacy of Racism

Although most of it is destroyed, the areas where Little Manila once existed are still overburdened by a lack of investment and opportunity and suffer from a legacy of pollution. The same is true in other places. Formerly redlined neighborhoods are still among the most polluted and disenfranchised.

Of the top ten most polluted and socioeconomically burdened census tracts, seven are in the Central Valley, the majority of which are located in Fresno and Stockton.

Map Legend

I created the following slider to show the relationship of redlining and these newly created maps. On the left are the redlining maps from the 30s and 40s, which impeded investment on communities of color (highlighted in red). The green and blue areas are the “most desirable.” On the right is a map from CalEnviroScreen, a science-based tool prepared by CalEPA’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA). The mapping tool uses environmental, health, and socioeconomic information to produce scores for every census tract in the state to compare different communities in a more equitable manner. Over 20 indicators contribute to this tool including ozone pollution, groundwater contamination, pesticides, traffic, asthma rates, education level, language isolation, and more.

Essentially, a red area with a high score experiences a much higher pollution and socioeconomic burden than green areas with low scores.

Sacramento’s West End continues to be disproportionately polluted and socioeconomically burdened places in California. East Sacramento, Land Park, Curtis Park, and Arden Village (not pictured) are all some of the least polluted and expensive places in Sacramento as well as least racially diverse, with over two-thirds of the population being white.

Stockton’s downtown is home to two of the ten most polluted neighborhoods in the State (outlined in blue). Both are at the crossroads of the Crosstown Freeway and I-5. Some of the more affluent neighborhoods in Stockton have retained their status since the 30s, South of University of the Pacific (UOP), around American Legion, East of Victory Park, Brookside, Spanos (not pictured), and Lincoln. Although Stockton is predominantly Hispanic, those neighborhoods are the least racially mixed. South of UOP is the only census tract with a slight majority white population in Stockton.

Fresno claims half of the ten most burdened communities in California (outlined in blue). Here you can see most of the city in red, with the least burdened neighborhoods further north and east, away from the city center. Zooming out on the image below, places like Clovis, Gordon, North & Southeast Growth Area, Bullard are some of the suburbs that continue to expand Fresno’s borders. These suburbs have the highest real estate value, least amount of pollution, and whitest population (nearly 80% in some places).

Don’t take my word for it, explore the redlining maps here, or check out CalEnviroScreen for yourself.

As you can see, we still feel the legacy of these discriminatory practices. The explicit racism has become implicit, or unconscious.

We continue to see implicit policies such as predatory lending by banks targeting people of color and low-income communities, burdening them with high interest rates that led to more dispossession and neighborhood instability, especially after the 2008 mortgage crisis. The hardest hit places for the house market crash were in the Central Valley: Fresno, Modesto, Bakersfield, Sacramento, and Stockton, the largest city to go bankrupt right before Detroit.

My family was a victim of these loans that targeted minorities and first-time home buyers. Almost everyone I know has a family member who lost their home.

People of color and low-income communities continue to be disproportionately affected by environmental and socioeconomic issues as they face a lack of resources, education, time, and opportunities to engage. It’s a vicious cycle.

TL;DR

Government had some racist policies in real-estate for 30 years that still impact low-income communities and neighborhoods of color 50 years after those policies were made illegal.

This post is part of a loose series, to see the first part click here. In our next story, we’ll dig a little deeper into the world of environmental justice, what it means, the effects of living in these neighborhoods, and what we can do about it.